Evocative Imperial Objects

Click in the PDF icons to access the publication "Picturesque Geography of Colombia, The Nueva Granada Seen by Two French Travelers of the Nineteen Century"

(Part 1 and Part 2)

Le Tour du Monde published at least two fascicles about Colombia (called La Nueva Granada at the time) “Voyage a la Nouvelle Granade” featuring Charles Saffray, a French doctor that traveled through Nueva Granada around 1861 and America Equinoxial: The Journey of Eduard André, a commissionaire of the French Government that visited the country between 1875 and 1876. It was reedited in Colombia in 1968 as a facsimile book entitled “Picturesque Geography of Colombia, The Nueva Granada Seen by Two French Travelers of the Nineteen Century” perhaps a more accurate title for these traveler’s stories.

The process of mediation and circulation of those images was complex and carefully curated. The engravings were made by famous artisans in Europe that reinterpreted the author’s sketches and texts, to produce images that were apt for the European publication standards and taste. The traveler’s interlocutor was the illustrated European man, he wrote directly to him. In that sense, I am not part of that ‘we’.

According to Jorge Orlando Melo a Colombian historian, the XIX century traveler writes to:

Sherry Turkle’s book Evocative Objects, Things We Think With invites us to think and feel through, with, and about objects as fundamental carriers, materializations, connectors, and producers of human experience. The overall assumption is that objects are companions to our emotional lives in the everyday and stimulators of our intellectual practice: “We think with the objects we love; we love the objects we think with" (p. 5). The book’s aim is to connect emotions and thought using personal narratives that reflect on objects as performative things that shape our intimate and social worlds. However, the book naturalizes the western white experience as a universal experience, and that, I can’t accept. This is truth not only because the authors are overwhelmingly white and the theoretical references painfully Eurocentric, but because there is a condescending tone when referring to 'other' experiences. Let us take, for instance, Turkle's reflection on the essay entitled The Radio by Julian Beinard, perhaps one of my favorite essays of the book because I see worlds that relate to my own:

Evocative Imperial Objects

What I am is what they see. The colonizers gaze.

Julian Beinart saw a new object, a mute radio made of wood, and then he could not stop seeing it. His hometown of Durban, South Africa, revealed itself to be rich in technological objects fashioned from the raw materials of an impoverished culture. There were bicycles made from beer cans, cars from bent wire, radios from wood—all technologies of everyday life copied as pure form. As Beinart found these objects, he saw people and social relationships of which he had been previously unaware. The mute radio and its cousins changed the people who made them and Beinart who discovered them. The mute radio, with no instrumental purpose, was free to serve as commentary on possession and lack, on power and impoverishment (p. 312).

Authors of Evocative Objects (The MIT Press) . The MIT Press. Kindle Edition. Edited by Sherry Turkle.

In this passage, Turkle fails to see creativity and invention in the people who create and transform objects. She is unable to see an active and performative relationship of the South Africans with a world of supposedly ‘finished’ objects, and instead sees mere copies with no functional value in a context of generalized impoverished culture. All the action is placed in the objects that transform people, and of course, on the author that "discovers" them (both the people and the objects). Julian Beinart is a subject of thought, contrary to those people defined by lack and impoverishment. The inventors and their objects are raw material, the author produces finished goods.

Turkle argues that there is a universal evocative power of objects but the meaning of such objects shift with time, place, and differences among individuals. Nevertheless, these differences seem to be related to personality (some people find mommies fascinating while others find them terrifying), but not with structural power differences in terms of race, gender and class. If the ‘we’ in “Things We Think With” (the book’s subtitle), is actually a group of white professors of MIT and Harvard, then is not my ‘we’. I am part of the book’s ‘they’ that is defined by lack, impoverishment and certain naiveté, a ‘they’ that is transformed by its objects and the discoveries of civilized architects. The authors’ gaze is the gaze of the settlers, the objects are read from and reproduce whiteness, but the book presents itself as a diverse array of objects and experiences in general.

The collection Evocative Objects is a medium that reproduces the settlers’ gaze, one that re/present whiteness, colonization and individualism as natural, neutral, and desirable. Is a way of knowing that divides the world between we (those who look/know) and them (those that are looked at/are objects of thought). As a Colombian non-white, non-American, non-professor of the MIT or Harvard, kind of person, I am part of 'them', those that are looked at but are not bearers of the look. For those of our kind, we can only see Turckle’s collection as an evocative imperial object that brings back previous examples of objects/media that naturalizes western white experience as a universal prescriptive experience.

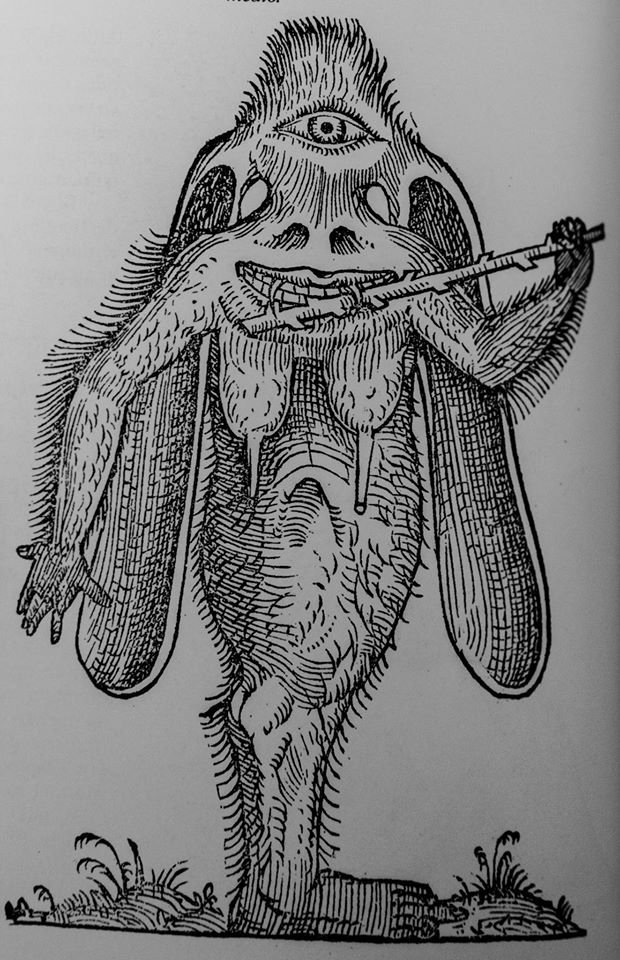

The image of ‘curious’, picturesque and monstrous people from far-away-lands is a tradition of the imperial west, a tradition that imagines an uncivilized other and a virgin territory to be conquered. The chronicles of the XVI century showed with texts and images the adventures of conquistadores in the New World, these images and cultural products were consumed by Europeans and represented the colonial relationship between the metropolis and the periphery. In the XIX century, a similar form of publication was in fashion, Le Tour du monde (Around the world), consisted on engravings and short texts that portrayed long and lonely journeys of voyagers in the savage jungles of the Americas, Africa and Oceania to discover possible markets and raw material to be extracted. It was directed to a broader French public as it was published in weekly collectible fascicles that circulated through the rail system network and every six months as book.

What I am is what they see.

What I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is What I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is What I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is What I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is What I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is w

CONTINUE IN NEXT ROW

Establish the difference between the civilized world and the wild world, and to outline and anticipate a program of annexation of the wild world by a central European culture. Colonialism is closely linked to a racist vision, which affirms the natural superiority of whites over blacks or Indians, or over the new races arising from their mix. And it is usually accompanied by machismo, revealed in the suggestive descriptions of tropical women”

Indeed, in “Voyage a la Nouvelle Granade” and America Equinoxial the travelers describe natives as ‘a beautiful and barbarian race’ and depict people, plants and animals as ‘picturesque’ and sensual landscapes that are part of an overall cultural imaginary of the savage other. The portraits of Indians and ‘Blackys’ (as the authors refers to black people) are accompanied by a description of their physical features, costumes and customs. In some images we can see the fight between two tropical animals: a jaguar v. a snake, a ‘blacky’ v. an alligator, a ‘blacky’ v. a shark. In other images, a tropical landscape, immense mountains, undomesticated rivers, fierce animals, tits, many Black, Mulatto, and Indian’s tits.

As I am not a XIX century French railroad user, or a voyager, I am not part of the ‘we’ intended for the publication, I am the other, the brown tits depicted both with lust and scientific disinterest. My ancestors’ images, are part of the imagination of a traveler that sketched what he experienced and the engraver that reinterprets and adjust those sketches to produce images suitable to the European taste in the XIX century.

According to Santiago Muñoz Arbelaez, the images and texts of Le Tour du Monde rather than being mere neutral representations are actually imperial objects that:

“(…) along with museums, royal gardens and curiosity cabinets - exhibited other cultures and geographies. (…). In the transit from sketch to engraving, the images became links in the global networks that articulated both sides of the Atlantic. They were thus transformed into imperial objects that offered an interpretation of other geographies and cultures, and evoked the presence and meaning of the other shore of the Atlantic”

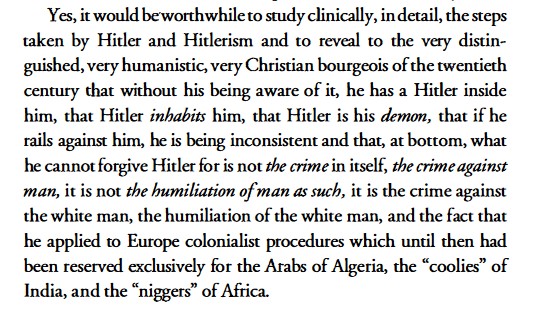

The publication Le Tour du Monde is an imperial evocative object, just as the book Evocative Objects. However, the latter, drunk in liberal vocabulary, fails to recognize the colonizers gaze that infects its discourses and silences. This critique should not be read as a suggestion to merely include ‘more’ voices of black people, people of color or from the Global South in the collection, but to acknowledge their colonial positioning, asking themselves in Donna's Haraway terms “With whose blood were my eyes crafted? ” Or, in Aime Cesarie’s words:

What I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is What I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is What I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is What I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is What I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is w

CONTINUE IN NEXT ROW

It is precisely this “sordidly racist” WE implicit in Evocative Objects that I believe should be acknowledged and confronted. If the non-white world accepts the invitation of the editor to produce and read media theory from the intimate and emotional worlds of the authors/readers, I can’t but read with disappointment that Evocative Objects, is yet another example of the naturalization and universalization of the white gaze and the centrality of white experience in media theory. Following McLuhan’s argument that the medium is the message or that the content of any medium always constitutes the content of other media, this essay aimed at denaturalizing the white supremacist settler’s gaze that is content and medium of travel publications of the XIX century and recent publications on technology and society. Thus, I propose a slight change in the book's title:

Evocative [imperial] Objects [in the West (perhaps just Massachusetts?)]: Things We [professors of MIT and Harvard] Think With.

Click in the Image to access to Discourse on Colonialism by Aime Cesarie

What I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is What I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is What I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is What I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is What I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is what theyWhat I am is w

BACK TO INTRO

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Césaire, Aimé. Discourse on Colonialism. [in English] Edited by Robin D. G. Kelley. New York :: Monthly Review Press, 2000.

Evocative Objects : Things We Think with / Edited by Sherry Turkle. Edited by Sherry Turkle. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2007.

Haraway, Donna. "Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism as a Site of Discourse on the Privilege of Partial Perspective ". Feminist Studies 14 (1988): 575-99.

Melo, Jorge. La Mirada De Los Viajeros Franceses En Colombia, Siglo Xix. 2001.

Muñoz Arbelaez, Santiago. "Las Imágenes De Viajeros En El Siglo Xix: El Caso De Los Grabados De Charles Saffray Sobre Colombia." Historia y grafía (2010): 165-97.

BACK TO INTRO